from our colleagues at ...

From Left to Right: Wendy Mendoza, Director of Student Development; Dawn S. Reese, Chief Executive Officer; Payal Avellan, Director of Communications and Marketing; Erin Hiebert, Communications and Marketing Associate; Tianna Haradon, Development Manager; Jerardo Reyes, Student Support Services Advisor; Jennifer Bassage Bonfil, Dance Education and Curriculum Specialist; Nelie Ramirez Peña, College Preparatory Coordinator; Keegan M. Bell, Chief Development Officer; Veronica Avzaradel, Controller; Ben Tusher, Director of Production and Operations. (Not pictured: Derek Bruner, Strategic Operations Administrator; Ernie Cabral, Student Development Associate; Teresa Farias, Family Services Manager; Dio Lopez, Student Support Services Mentor; Ruby Osoria, Student Development Middle School Advisor.)

THE WOODEN FLOOR

Dawn S. Reese, Chief Executive Officer, The Wooden Floor, writes:

At The Wooden Floor, we transform the lives of young people in low-income communities through the power of dance and access to higher education. 100 percent of students who graduate from The Wooden Floor immediately enroll in higher education. We use a long-term approach grounded in exploratory dance education to foster the confidence and gifts within each child, all of whom are encouraged to stay at TWF for 10 years. As an organization with an enduring commitment to assessment and evaluation, we embarked on a longitudinal study in 2013 with The Centers for Research on Creativity (CRoC), to assess the impacts of our dance-centric model on students over 10 years, mirroring the length of time a student might participate in TWF programs, between third and twelfth grade. TWF looked for a partner willing to develop assessment tools specific to the organization’s ecosystem that not only had expertise in arts evaluation and assessment but also had expertise in evaluating youth development outcomes.

CRoC was interested in the potential of this study because the field of dance education is comparatively ‘under-studied’ in contrast to the visual arts, music, and theatre education programs. They were also keen to explore a long-term study design. The 10-year time span offered an almost unprecedented look into a dance education program.

From an organizational perspective, TWF programs may evolve in response to the data as we employ a continuous cycle of improvement to advance effectiveness and sustain our high-impact outcomes. The study data will also inform our strategic planning, organizational decision-making, and the impact story we can share with current and potential stakeholders.

The study will also advance our goals to scale our model locally and nationally. Locally, TWF will open its second location, serving 100 new students who will be enrolled in the longitudinal study, further informing our decision making. Nationally, TWF signed our first national licensed partner, CityDance DREAM in Washington, DC, in November 2015. Under a copyright license agreement, TWF provides curriculum, training, and consulting on its program model, as well as effective creative youth development strategies, and CityDance DREAM agrees to implement TWF’s theory of change and programmatic model in full. Once CityDance DREAM implements the full programmatic model, their own cohort of students will be encouraged to participate in the longitudinal study to analyze the effectiveness of its programs for their specific population group.

Outside of our organization, our data will continue to inform academic and social developments for years to come, with additional waves of data entering the database. The results may be disseminated to other not-for-profit organizations to help the advancement of youth development models. Ultimately, as the study progresses, factors that help close the achievement and other gaps will be discovered. Through the course of this study, the researchers anticipate that the data will illuminate appropriate indicators of success in the realm of creative youth development, positive changes over time among those who participate in intervention programming, and elements of curriculum and instruction that correlate to positive changes in student development.

We believe in the power of dance as a catalyst for personal change and empowerment, which moves young people forward with the confidence and gifts to know that, from here, students can step anywhere. We will know more and more about just where they step as the study proceeds. Our hopes are this collaboration with CRoC will serve as a landmark study nationally to validate the tangible results of dance immersion in creative youth development outcomes. The data will help inform the scaling of our model both locally and nationally to transform more young people in low income communities across the nation. Lastly, we are certain that it will serve as a hallmark study giving voice to the power of dance.

At The Wooden Floor, we transform the lives of young people in low-income communities through the power of dance and access to higher education. 100 percent of students who graduate from The Wooden Floor immediately enroll in higher education. We use a long-term approach grounded in exploratory dance education to foster the confidence and gifts within each child, all of whom are encouraged to stay at TWF for 10 years. As an organization with an enduring commitment to assessment and evaluation, we embarked on a longitudinal study in 2013 with The Centers for Research on Creativity (CRoC), to assess the impacts of our dance-centric model on students over 10 years, mirroring the length of time a student might participate in TWF programs, between third and twelfth grade. TWF looked for a partner willing to develop assessment tools specific to the organization’s ecosystem that not only had expertise in arts evaluation and assessment but also had expertise in evaluating youth development outcomes.

CRoC was interested in the potential of this study because the field of dance education is comparatively ‘under-studied’ in contrast to the visual arts, music, and theatre education programs. They were also keen to explore a long-term study design. The 10-year time span offered an almost unprecedented look into a dance education program.

From an organizational perspective, TWF programs may evolve in response to the data as we employ a continuous cycle of improvement to advance effectiveness and sustain our high-impact outcomes. The study data will also inform our strategic planning, organizational decision-making, and the impact story we can share with current and potential stakeholders.

The study will also advance our goals to scale our model locally and nationally. Locally, TWF will open its second location, serving 100 new students who will be enrolled in the longitudinal study, further informing our decision making. Nationally, TWF signed our first national licensed partner, CityDance DREAM in Washington, DC, in November 2015. Under a copyright license agreement, TWF provides curriculum, training, and consulting on its program model, as well as effective creative youth development strategies, and CityDance DREAM agrees to implement TWF’s theory of change and programmatic model in full. Once CityDance DREAM implements the full programmatic model, their own cohort of students will be encouraged to participate in the longitudinal study to analyze the effectiveness of its programs for their specific population group.

Outside of our organization, our data will continue to inform academic and social developments for years to come, with additional waves of data entering the database. The results may be disseminated to other not-for-profit organizations to help the advancement of youth development models. Ultimately, as the study progresses, factors that help close the achievement and other gaps will be discovered. Through the course of this study, the researchers anticipate that the data will illuminate appropriate indicators of success in the realm of creative youth development, positive changes over time among those who participate in intervention programming, and elements of curriculum and instruction that correlate to positive changes in student development.

We believe in the power of dance as a catalyst for personal change and empowerment, which moves young people forward with the confidence and gifts to know that, from here, students can step anywhere. We will know more and more about just where they step as the study proceeds. Our hopes are this collaboration with CRoC will serve as a landmark study nationally to validate the tangible results of dance immersion in creative youth development outcomes. The data will help inform the scaling of our model both locally and nationally to transform more young people in low income communities across the nation. Lastly, we are certain that it will serve as a hallmark study giving voice to the power of dance.

COLLABORATIONS: TEACHERS AND ARTISTS (CoTA)

Dennis Doyle, Ed.D., offers a synopsis of his organization's three year partnership with CRoC in San Diego, CA. CoTA paired individual teaching artists with individual teachers to create multiple teaching plans that were introduced weekly in classrooms and watched closely by CRoC researchers.

Three years ago the board of directors of Collaborations: Teachers and Artists (CoTA) formulated an enticing question: What could we learn if we developed three entire elementary schools as arts integration centers of practice in San Diego County over a three year period of time? We wondered out loud what distinguished researchers might learn from CoTA’s professional development process, what the impact would be on teachers and students, and how we would measure growth.

With commitments from two foundations, CoTA’s board and staff developed a request for applicants and 30 elementary schools responded to the opportunity to answer those questions. Ultimately the candidates were whittled down to three finalists. All teachers at the selected sites would be trained for 10 weeks through one-to-one collaborations and hands-on workshops with artists. In exchange, third grade students would be assessed each year through fifth grade and teachers, principals and children would allow their learning to be transparent.

Teachers at each school had to vote, with a minimum of 80% in favor, in order to take part.

Seeking both a qualitative and quantitative assessment, CoTA contracted with Centers for Research on Creativity (CRoC) to measure student growth using CRoC’s Next Generation Creativity Survey. In addition ethnographic field work conducted by research associates using classroom observations, surveys and interviews would document changes in pedagogy and consequent shifts in school culture.

Three years later CoTA is reaping the results from this intensive professional development and documentation. The three Beacon Schools: Park Dale Lane Elementary School in Encinitas (north San Diego county), Flying Hills Elementary in Cajon Valley Union School District (east county) and Kellogg Elementary School (south county) are yielding a wealth of significant outcomes.

We saw significant quantitative student gains following the student cohort from third grade to fourth grade in the first two years, with large gains on NGCS scales measuring critical thinking, empathy and collaboration - all essential cornerstones for innovation and creativity. Of equal importance were the qualitative conclusions capturing rich descriptions of mechanisms of change for both students and teachers.

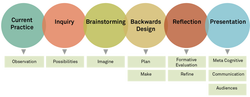

Enduring changes in teaching and learning occurred when the teacher’s current practice was observed without judgment before new arts integration methods were introduced. Once a safe and secure, evaluation-free environment was established, teachers were willing to be vulnerable and to consider new pedagogical possibilities.

Inquiry was a vital strategy for CoTA artists who introduced arts integration by asking questions instead of defaulting to telling teachers what to do. Success was linked to a sense of agency on the part of teachers - unlocking possibilities; imagining the project-based collaboration; designing the unit with the end in mind; and transitioning from being co-planners to makers.

Weekly reflection allowed ongoing refinement, with a focus on engagement of previously disengaged students. This emphasis, we learned from CRoC, put a focus on developing new roles for students who had not been active participants and allowed for new opportunities among English learners and special needs students.

Finally, presentation was important, not only to communicate with specific audiences, but to spawn meta-cognitive awareness. Students, teachers and CoTA artists know what they have learned and how they learned it.

Indeed, the mechanisms of change seemed to work in parallel both for teachers and students. The degree to which teachers were willing to tap into their own creativity appeared to better equip teachers with the capacity to engender more creativity in their students.

In summary, we wondered if the same mechanisms of change could be applied to other constituencies in the ecology of education. Presently we are prototyping parent classes going from inquiry to presentation. Principals have presented the work at their schools in panel discussions at conferences, and school board

members and superintendents have presented the Beacon School work at professional meetings, allowing for reflection, dissemination and broader engagement.

Tuning protocols have also been introduced, whereby teachers share their CoTA units with each other, actively borrow ideas, and give each other positive coaching on a quarterly basis. Artists also use an adapted tuning protocol as a method for continuous improvement.

CoTA’s iterative approach to professional development over three years allows for a gradual release of responsibility, moving from artist-led to teacher-led units and, as CRoC has observed, posing the greatest likelihood for sustained and enduring arts integration strategies in classroom teacher practice.

Three years ago the board of directors of Collaborations: Teachers and Artists (CoTA) formulated an enticing question: What could we learn if we developed three entire elementary schools as arts integration centers of practice in San Diego County over a three year period of time? We wondered out loud what distinguished researchers might learn from CoTA’s professional development process, what the impact would be on teachers and students, and how we would measure growth.

With commitments from two foundations, CoTA’s board and staff developed a request for applicants and 30 elementary schools responded to the opportunity to answer those questions. Ultimately the candidates were whittled down to three finalists. All teachers at the selected sites would be trained for 10 weeks through one-to-one collaborations and hands-on workshops with artists. In exchange, third grade students would be assessed each year through fifth grade and teachers, principals and children would allow their learning to be transparent.

Teachers at each school had to vote, with a minimum of 80% in favor, in order to take part.

Seeking both a qualitative and quantitative assessment, CoTA contracted with Centers for Research on Creativity (CRoC) to measure student growth using CRoC’s Next Generation Creativity Survey. In addition ethnographic field work conducted by research associates using classroom observations, surveys and interviews would document changes in pedagogy and consequent shifts in school culture.

Three years later CoTA is reaping the results from this intensive professional development and documentation. The three Beacon Schools: Park Dale Lane Elementary School in Encinitas (north San Diego county), Flying Hills Elementary in Cajon Valley Union School District (east county) and Kellogg Elementary School (south county) are yielding a wealth of significant outcomes.

We saw significant quantitative student gains following the student cohort from third grade to fourth grade in the first two years, with large gains on NGCS scales measuring critical thinking, empathy and collaboration - all essential cornerstones for innovation and creativity. Of equal importance were the qualitative conclusions capturing rich descriptions of mechanisms of change for both students and teachers.

Enduring changes in teaching and learning occurred when the teacher’s current practice was observed without judgment before new arts integration methods were introduced. Once a safe and secure, evaluation-free environment was established, teachers were willing to be vulnerable and to consider new pedagogical possibilities.

Inquiry was a vital strategy for CoTA artists who introduced arts integration by asking questions instead of defaulting to telling teachers what to do. Success was linked to a sense of agency on the part of teachers - unlocking possibilities; imagining the project-based collaboration; designing the unit with the end in mind; and transitioning from being co-planners to makers.

Weekly reflection allowed ongoing refinement, with a focus on engagement of previously disengaged students. This emphasis, we learned from CRoC, put a focus on developing new roles for students who had not been active participants and allowed for new opportunities among English learners and special needs students.

Finally, presentation was important, not only to communicate with specific audiences, but to spawn meta-cognitive awareness. Students, teachers and CoTA artists know what they have learned and how they learned it.

Indeed, the mechanisms of change seemed to work in parallel both for teachers and students. The degree to which teachers were willing to tap into their own creativity appeared to better equip teachers with the capacity to engender more creativity in their students.

In summary, we wondered if the same mechanisms of change could be applied to other constituencies in the ecology of education. Presently we are prototyping parent classes going from inquiry to presentation. Principals have presented the work at their schools in panel discussions at conferences, and school board

members and superintendents have presented the Beacon School work at professional meetings, allowing for reflection, dissemination and broader engagement.

Tuning protocols have also been introduced, whereby teachers share their CoTA units with each other, actively borrow ideas, and give each other positive coaching on a quarterly basis. Artists also use an adapted tuning protocol as a method for continuous improvement.

CoTA’s iterative approach to professional development over three years allows for a gradual release of responsibility, moving from artist-led to teacher-led units and, as CRoC has observed, posing the greatest likelihood for sustained and enduring arts integration strategies in classroom teacher practice.

Graphic Depicts CoTA’s Mechanisms of Change